As dedicated followers of JavaScript fashion, we – the Guardian US interactive team – had been looking for an opportunity to experiment with Progressive Web Apps, or PWAs. ‘Progressive Web App’ is essentially a marketing term (like AJAX or ‘responsive design’) that encompasses a variety of techniques for creating experiences that rival native apps in terms of slickness, features and usability – most notably around offline support.

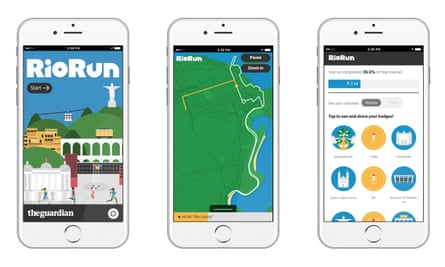

The Olympics gave us that opportunity in the form of RioRun, an interactive podcast that tracks your distance as you run outside (or on a treadmill) and translates it into progress along the marathon route through downtown Rio de Janeiro. As you run, you learn about the area you’re running through – its history, culture, politics, recent news events – while ambient audio recorded on location plays in the background.

Creating the experience as a PWA made sense for several reasons:

Because it uses geolocation, it needs to be served over HTTPS. For that reason, we opted to create a dedicated subdomain rather than serving the app from an article page on theguardian.com (which hasn’t yet fully transitioned to HTTPS)

There’s a lot of audio, some of which might start downloading after you’ve started running. For people in rural areas with patchy connectivity, or those with limited data plans, offline support is very useful

No-one (at least, no-one we know) is going to complete the experience in one go, so it’s far more likely that people will get through the whole route if the app can easily be saved to the home screen

It was not, however, without challenges.

Service workers, and how not to make them

The heart of a PWA is the service worker. Service workers are JavaScript files that sit between the browser and the network, responding to network requests (for example by serving cached responses) and handling background activity such as push notifications.

Chrome, Firefox and Opera all have good support for most service worker APIs. Edge (formerly Internet Explorer) is working on it. Safari is the conspicuous exception – iPhone and iPad users will have to wait a while before being able to take advantage of these new features.

Registering a service worker is straightforward:

if ( 'serviceWorker' in navigator ) {

navigator.serviceWorker.register( '/service-worker.js' )

.then( function ( reg ) {

console.log( '✓ service worker ready' );

});

}Inside the service worker we’re listening for three events – install (which happens whenever someone visits the page for the first time, or when a visitor returns after the service worker was updated), activate (which happens when no previous service worker is still active on the page), and fetch (which happens whenever a network request is made).

This lifecycle takes some getting used to, not least because it means that reloading the page no longer behaves the way most web developers are used to. Rather than replacing an obsolete service worker, as you might naively expect, reloading the page will keep the out-of-date service worker ‘in control’ – i.e. intercepting network requests – until you close the tab (and any others with the same page) completely. Meanwhile, if you need to clear the service worker’s cache, you have to remember to do a hard refresh (Cmd-Shift-R on a Mac). Until you understand what’s going on it’s a thoroughly maddening experience.

For a while, not understanding what was going on, we resorted to all sorts of mad hacks – randomising the service worker URL and so on – in an effort to see our changes reflected.

(We collected some of our notes together and shared them, and discovered that we’re not alone – many people have had the same frustrations, despite the wealth of tutorials and documentation available. The combined surface area of the new APIs is truly daunting, and it remains to be seen if an ecosystem of service worker libraries will ease the pain.)

Once you get there though, it’s quite magical when you load the page on a phone, switch it to airplane mode, reload, and continue using the app as though nothing was wrong.

Cache rules everything around me

We’re able to do that by caching all the files needed by the app (apart from the audio files) inside the install handler. The cache manifest is automatically generated during our build process, so we don’t need to worry about forgetting to add new icons etc as we add them to the app.

When we deploy a new version of the app, the cache is given a unique name, allowing us to free up the space taken by the old cache.

Audio is handled differently, because we don’t want to download all 92 .mp3 files (totalling around 125Mb) when the app starts. Instead, we cache those files progressively, storing them in a separate cache that survives the deployment of a new version of the app. A ‘preload audio files’ button allows runners to fetch the next several miles of audio – we judged that it would be better than downloading the whole lot, since the browser can delete the cache at any time in order to free up space. (Since launching, Google’s Alex Russell pointed us towards the Quota API which allows you to request additional permanent storage, but for now we prefer the partial approach as it’s less to ask of people who may not yet be fully committed to the app.)

Once an audio file is no longer needed (because we’ve passed the point on the route at which playback starts) we can safely discard it from the cache.

Don’t make the mistake we made – if you need to cache additional assets after the initial install event, you can access the service worker cache API as window.caches. There’s no need to send a message to the service worker and have it send progress messages back. That’s good, because client-worker messaging is hellaciously confusing.

No place like home

The URL bar is arguably the most powerful text-based interface ever devised, but getting to a web app on a mobile phone is still a cumbersome process. Typically you have to open the browser app (one tap), switch to tab view (another), press the ‘create new tab’ button (a third) then tap into the search box or URL bar (four!). Then you have to remember the URL and type it accurately on a tiny keyboard, hoping that the autocomplete doesn’t take you to an irrelevant deep link.

Native apps have a huge advantage: one tap and you’re in business.

PWAs help to close the gap by making it easier for web apps to appear on the home screen on Android. If certain criteria are met – HTTPS, a service worker, and a manifest file – the browser will prompt you to ‘install’ the app if it detects sufficient engagement (currently defined, by Chrome at least, as two visits more than 5 minutes apart, though this is subject to change).

The manifest file contains basic information about the app’s name, start_url and icons. It can also be configured to hide the URL bar (making it feel more ‘native’) or stick to a specific orientation (for example, RioRun only works in portrait mode – we have to resort to a ‘please rotate your screen’ message in a web browser if the phone is held landscape).

This information will also be used if you install the app manually, using the ‘Add to home screen’ option in the browser menu.

Once it’s on the home screen, it’s not only much easier for someone to use the app on an ongoing basis, but much more likely that they’ll remember to.

What’s next?

RioRun was a fairly unique storytelling experiment, and one that demands a lot from participants: not many pieces of journalism expect you to get changed into gym kit in order to experience them.

But we think that PWAs are potentially a perfect vehicle for all kinds of journalism – events like election night results, specific verticals like recipes, long-running investigations like The Counted – and we hope to see (and make) more in future.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion