Interested in learning JavaScript? Get my ebook at jshandbook.com

This tutorial explains what tools the Chrome and Firefox Dev Tools display that help you debug a Progressive Web App.

There’s a lot to learn about this topic and the new browser APIs. I publish a lot of related content on my blog about frontend development, don’t miss it! ?

What is a Progressive Web App?

First things first. A Progressive Web App (PWA) is an app that can provide extra features based on the device support, such as:

- The ability to work offline

- Push notifications

- An almost native app look and speed

- Local caching of resources

But it still works fine as a normal website on devices that do not support the latest tech.

A brief Chrome Developer Tools overview

Let’s start with Chrome. Once you open the DevTools, you see several panels. You might be familiar with many of those panels, like Console, Elements or Network. You use these daily when building web sites or web applications.

The Application panel is recent, but contains some familiar tools. In summer 2016, the Resources tab was renamed “Application.” This grouped all the features together that usually distinguish web applications from web pages. We’ll examine it in detail soon.

A real world example

This tutorial walks through an exploration of the Progressive Web App available at https://events.google.com/io2016/. You can open Chrome and do the exact same steps detailed here, without having to setup anything locally.

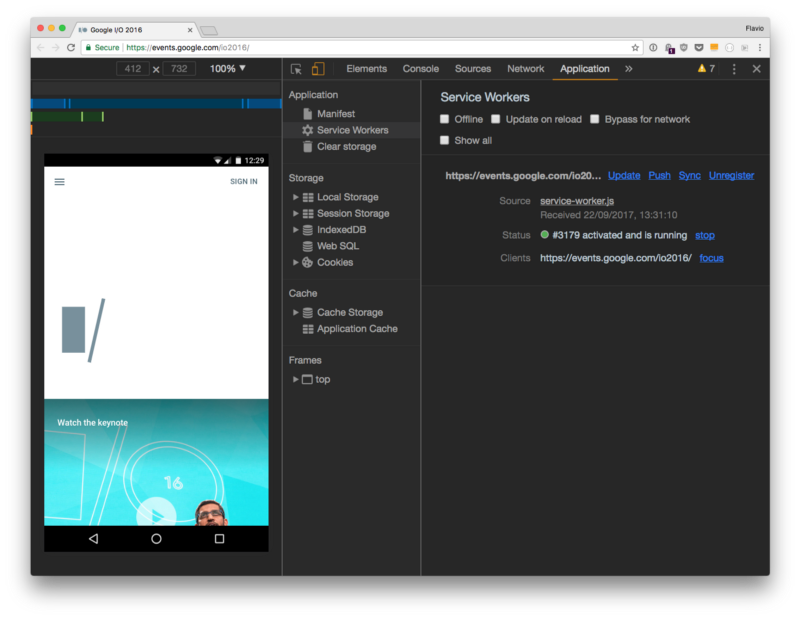

Simulate a device

Let’s first enable the Chrome DevTools Device Mode. This gives you the option to emulate a device in your browser. We choose an Android device, because currently PWAs only show their full potential on Android. Safari beginning work on supporting Service Workers seems a step in the right direction for iOS and Safari Desktop support.

The Application panel in details

The Application Panel groups many elements which are key to Progressive Web Apps.

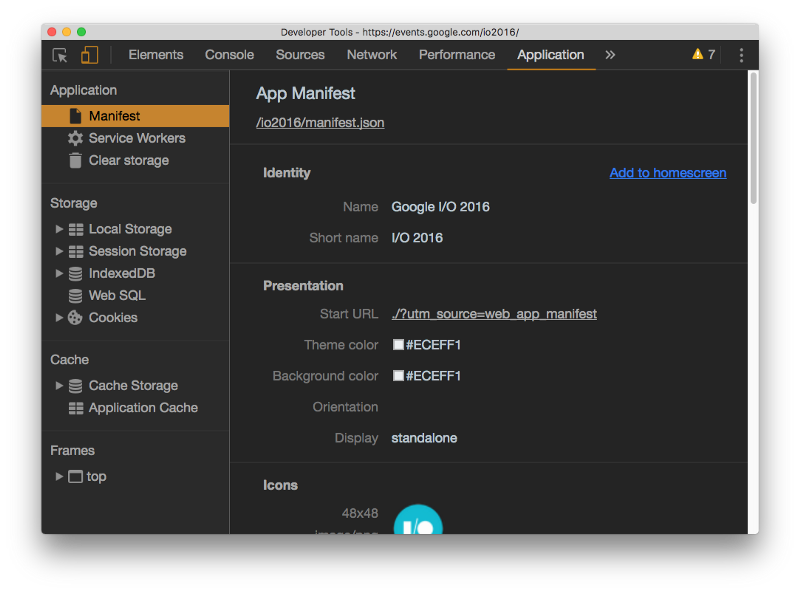

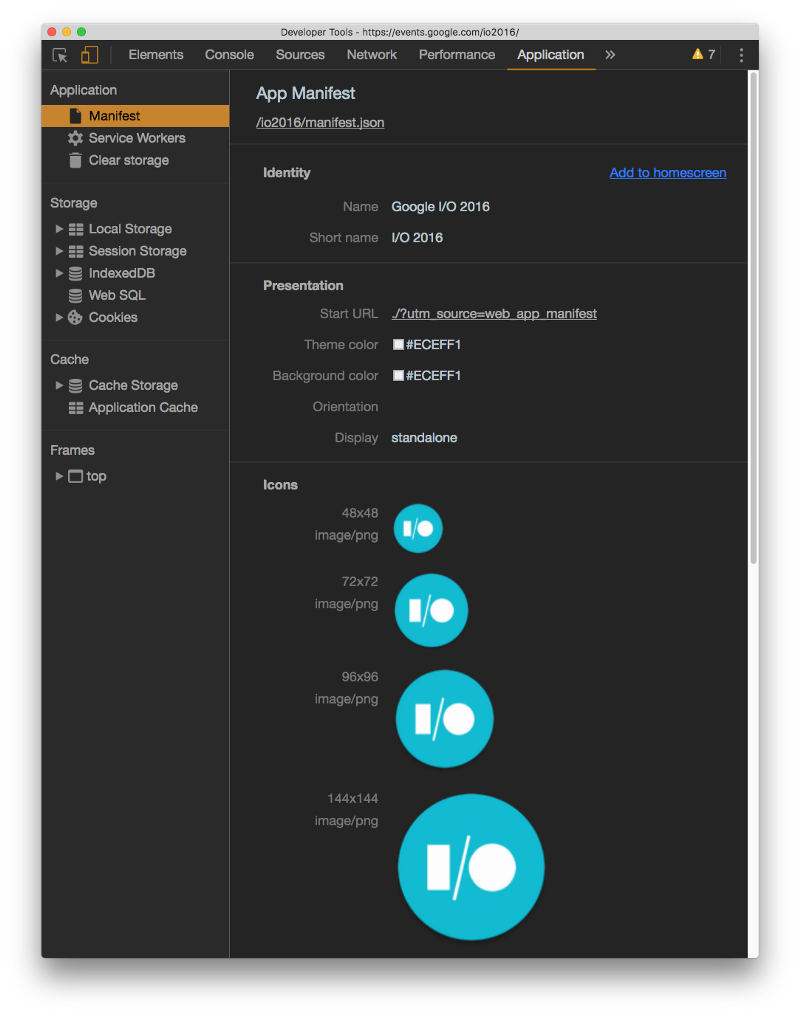

Manifest

The manifest unlocks the ability to offer users the Add to home screen option. It provides a series of details about how the app should behave once installed on the device. If there’s anything wrong with how you defined the manifest, it will report the issue.

There you see the name of the App, a short name for the home screen, icons preview, and some details about the presentation:

- Start URL: the URL that the device will load when the user launches the web app from the home screen. You can add a campaign identifier to segment the PWA accesses in the analytics.

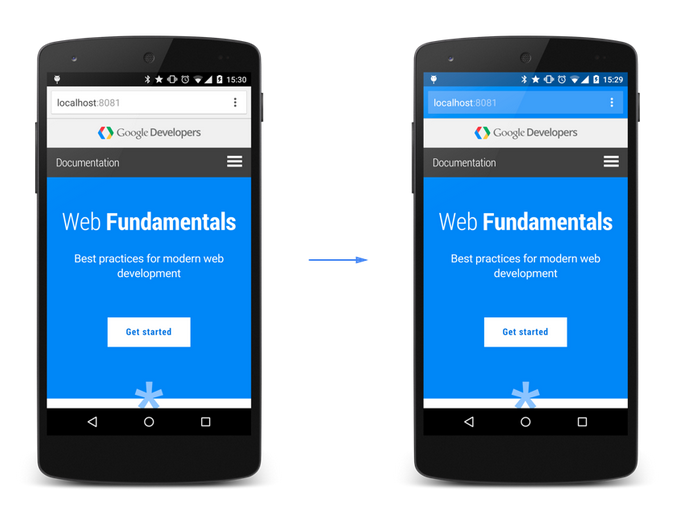

- Theme color: indicates a theme for your site. Chrome uses it to color some browser UI elements, such as the address bar. This can be customized per-page using the meta tag

<meta name="theme-color">, but specifying it in the manifest provides a site-wide theme color when the app is launched from the home screen.

- Background color: specifying the background color of your web app in the manifest allows the browser to show this color in the loading screen before the CSS is even available. This produces a nicer experience for the user. As soon as the CSS is available, this value is overwritten by the actual web app styling.

- Orientation: specifies the default orientation, and can be any value in

any,natural,landscape,portraitand other options detailed in the Screen Orientation API Working Draft. - Display: defines how the app is presented. Valid values are

fullscreenwhich open the app in the entire display size.standaloneshows the device standard status bar and the system back button.minimal-uiprovides the user at least the back, forward, and reload buttons. Andbrowsershows the normal browser UI which includes the address bar.

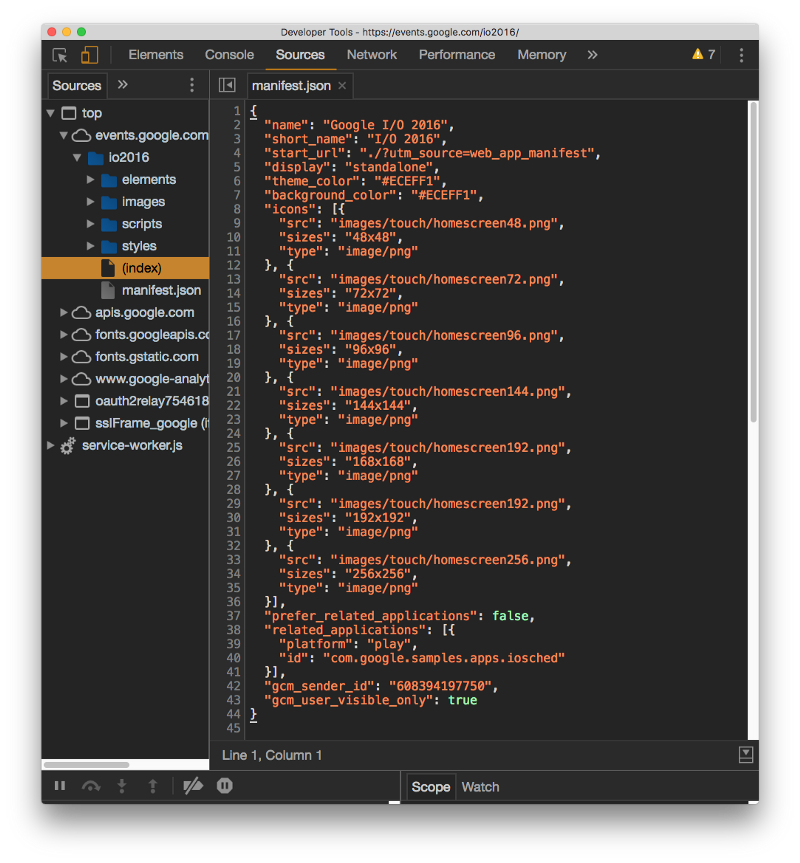

At the top of the Manifest tab, clicking the manifest.json link brings us to the Sources panel, with the full source of the manifest.

The Manifest allows you to define many other fields. I suggest looking at the Web App Manifest Working Draft directly to know more.

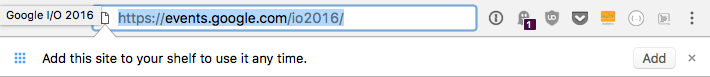

The last thing on this screen, which is quite important, is the Add to home screen link. On the Chrome Desktop, it triggers the browser to add the app to the shelf. On mobile, it prompts to install the app (add the icon to the home screen):

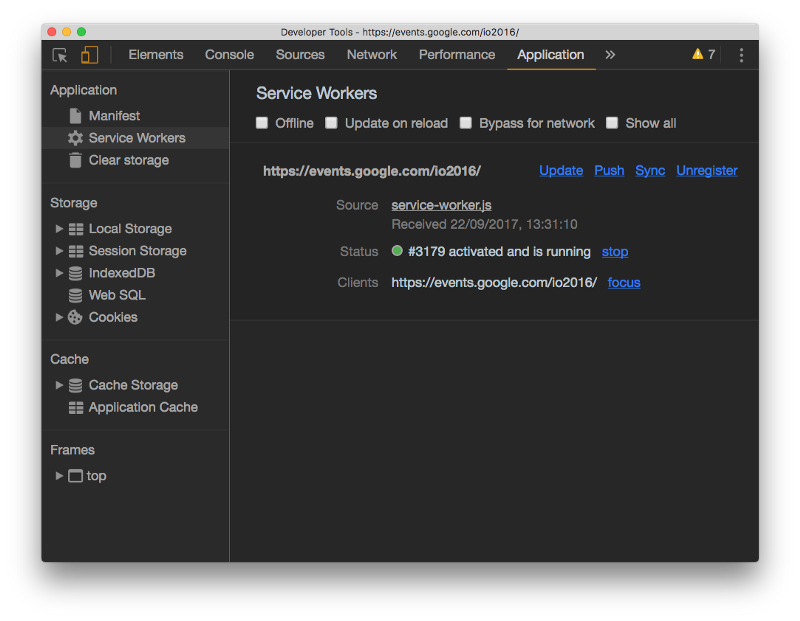

Service Workers

Next up in the list there’s the Service Workers tab. Service Workers are the technology that enables a PWA to work offline. They allow you to intercept network requests and to use the Cache API to store resources locally.

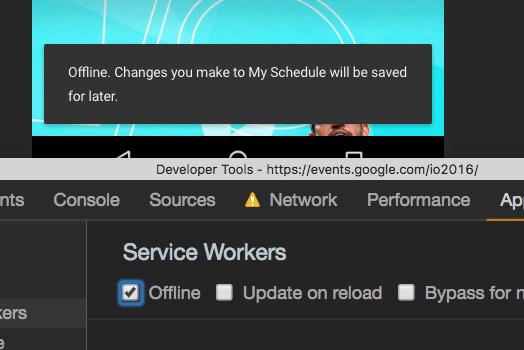

From this screen you can force offline mode in the tab by enabling the Offline checkbox:

Offline can also be forced in the Device Mode screen, in addition to network throttling.

Update on reload is very useful when debugging. Service Workers are installed on the device when they are first loaded. They are not updated until the Service Worker code changes, so they are not like regular resources.

But even if you update the service worker, it won’t be used by the web page until the old service worker can be removed — that is, until the user closes all the tabs that point to the web app. This checkbox forces the update.

Bypass for network allows you to completely turn off the caching enabled by the Service Worker. This prevents the app from using cached resources when you want a direct access from the network. Again, very useful when debugging.

Show all is an option that enables quick access to all the Service Workers installed on the device.

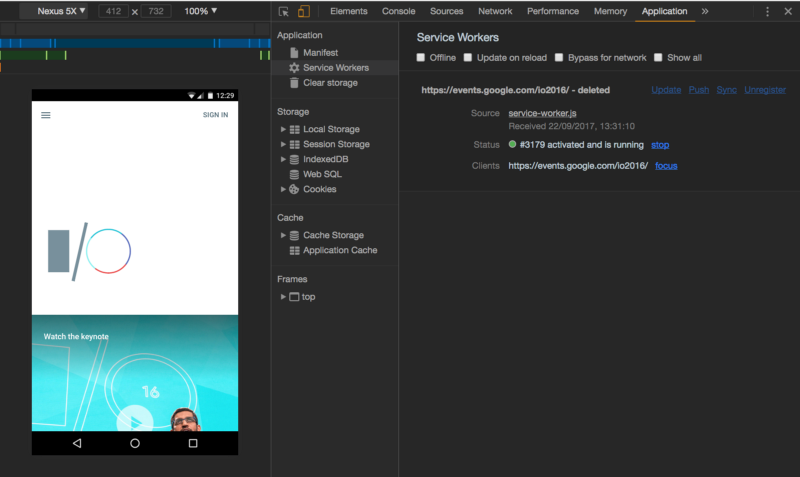

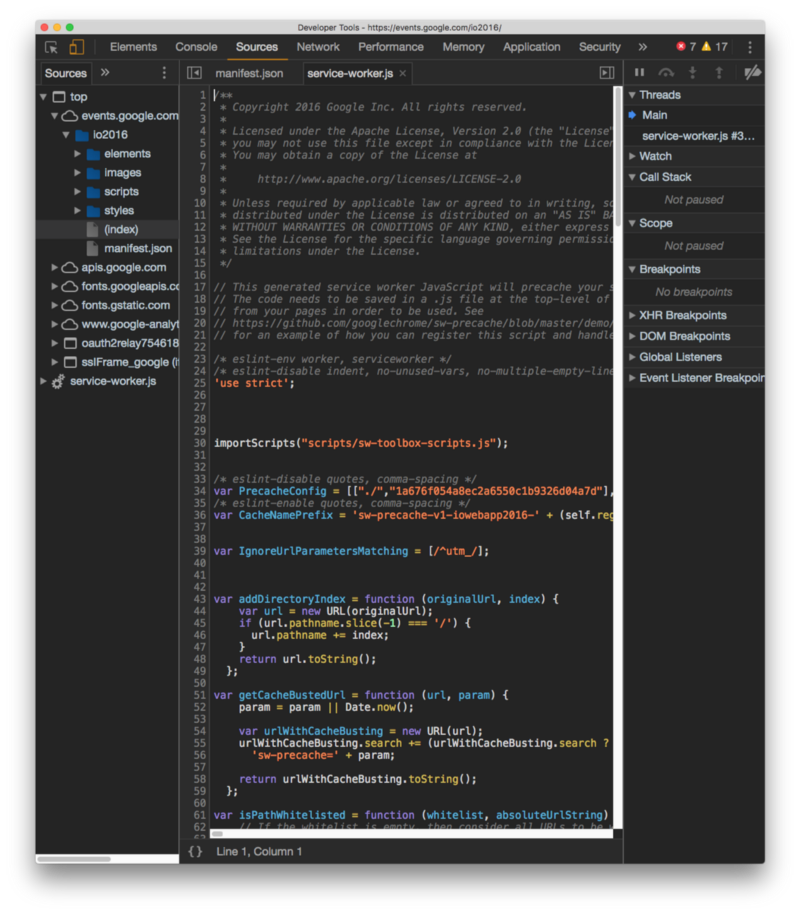

Each Service Worker is listed with a status indicator which you can stop and restart. By clicking the filename, you can inspect the source and hook into it using the built-in JavaScript debugger:

The thing you’ll likely use the most is the Service Worker Lifecycle Events simulation. You can force the following events:

- Update will force an update of the Service Worker

- Push emulates a push event

- Sync emulates a background sync event, which allows the user to perform actions offline and communicate them to the server once online

- Unregister unregisters the Service Worker, so you can start with a clean state

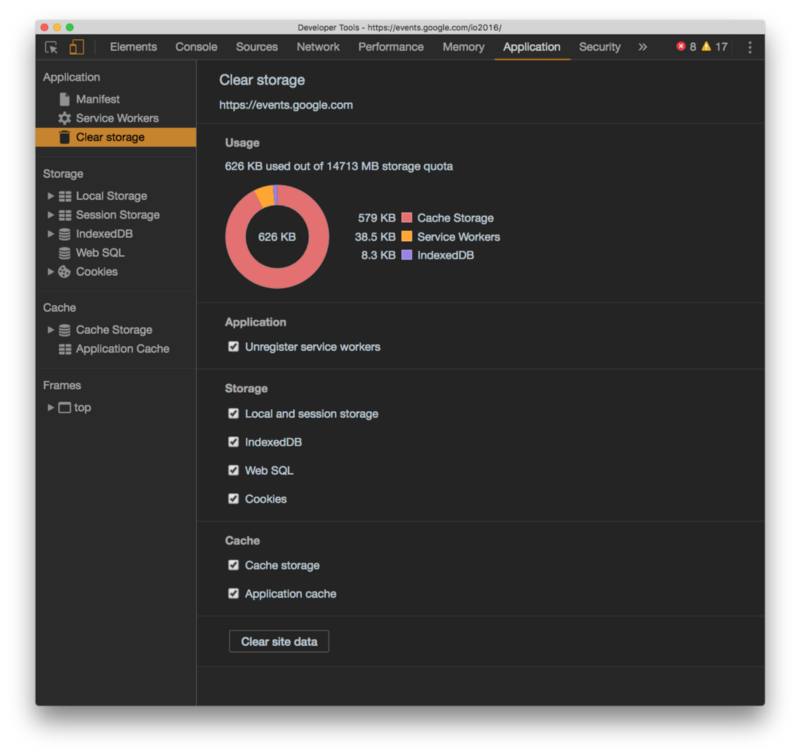

Clear storage

The Clear storage tab shows you the total storage size used by your web app, how much storage you have left, and allows you to cherry-pick which storage to clear.

Storage

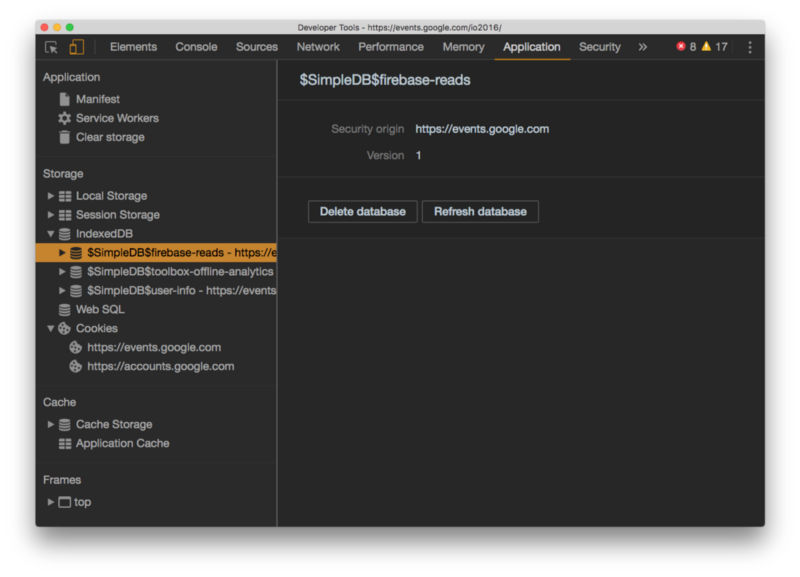

The Storage tab contains tools to interact with the usual storage options like Local/Session Storage, IndexedDB and Cookies. It is not unique to Service Workers, so I won’t get into the details of it here.

Cache

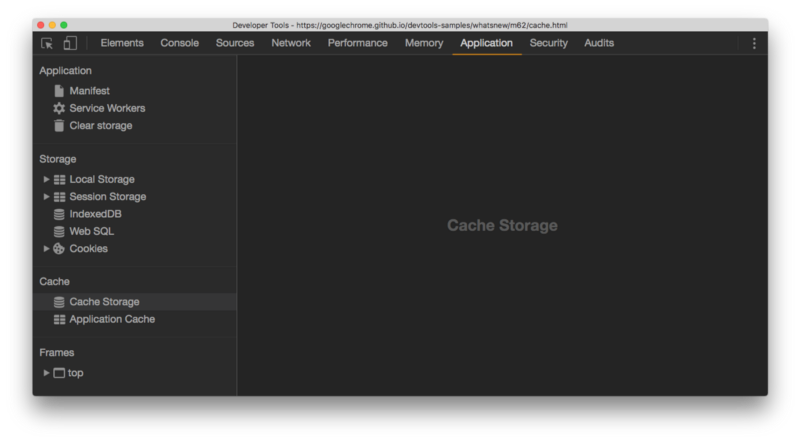

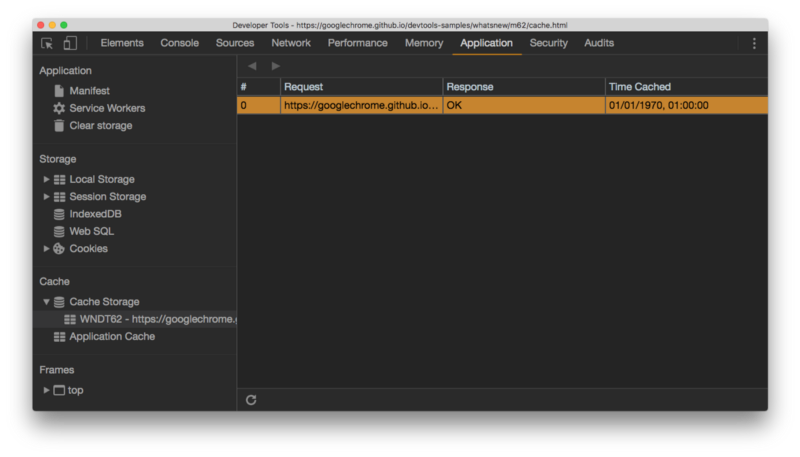

Ignoring the Application Cache tab — which is a deprecated tech — the Cache Storage tab is key to Service Workers. It shows the content of resources stored using the Cache API, part of the Service Workers spec. It’s not limited to use by Service Workers.

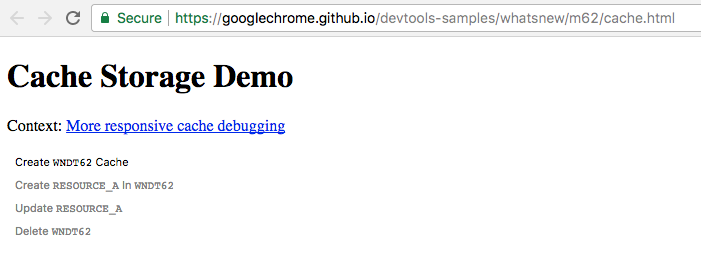

The Google Chrome Cache Storage Demo is a good way to see what happens when you add an item to the cache.

At first, the cache is not used at all:

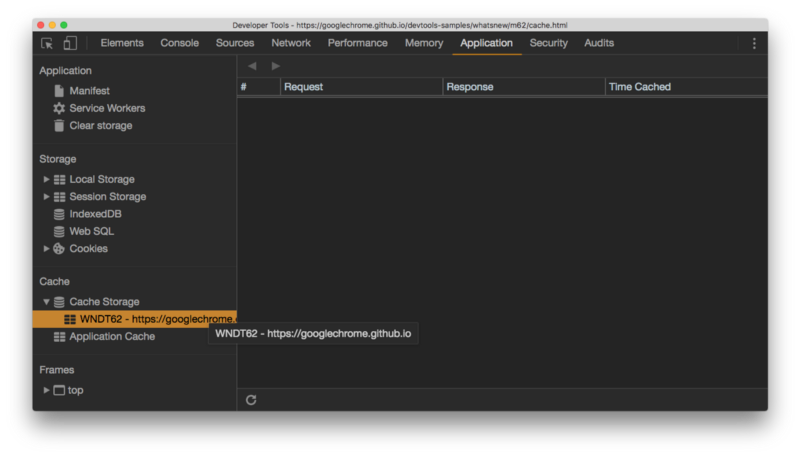

Pressing the Create WNDT62 cache button triggers the creation of the cache:

Then Create RESOURCE_A in WNDT62 adds an item into the cache:

Pressing Update RESOURCE_A increments the body value, which we can inspect using:

caches.open('WNDT62').then(function(cache) { return cache.match('RESOURCE_A').then((res) => { res.text().then(body => console.log(body)); })})Every time you press Update RESOURCE_A, the value returned is incremented.

Pressing Delete WNDT62 removes the cache, frees the space that was taken by the resources, and restores the initial state of the app.

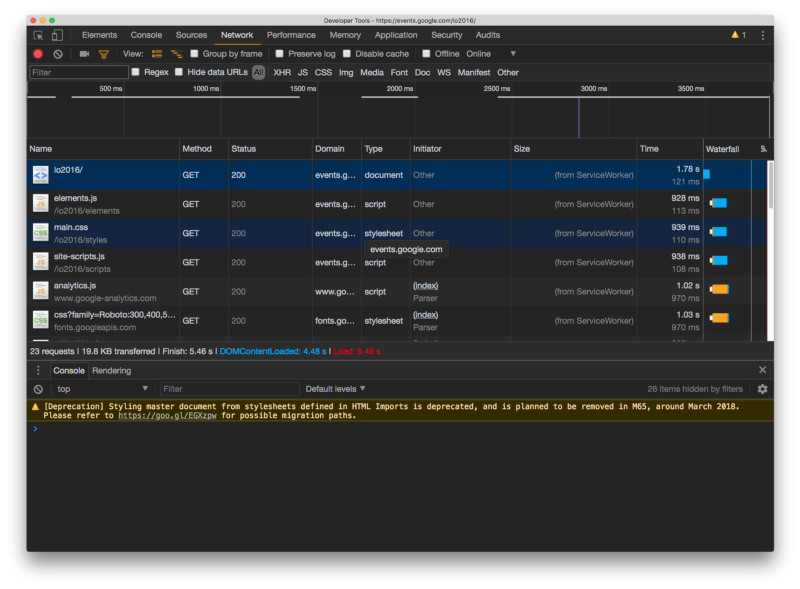

When loading resources cached by Service Workers using the Cache API, the Network Panel of the DevTools shows it as coming from Service Workers:

What about Firefox?

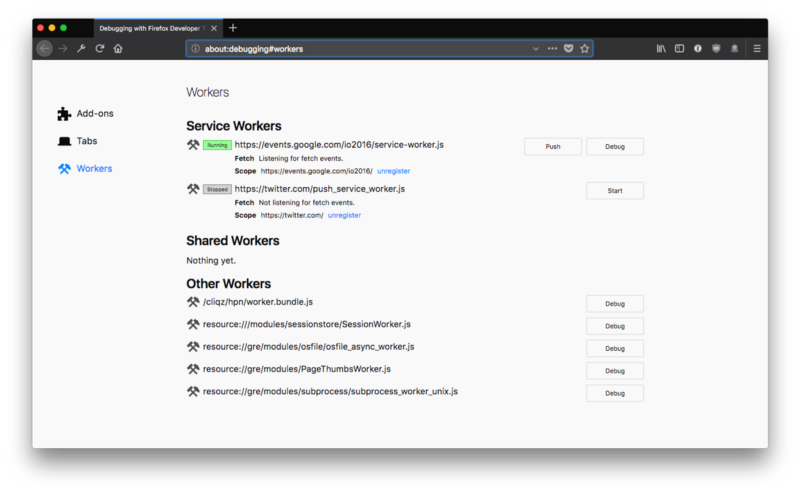

Firefox has great support for Progressive Web Apps as well as Service Workers. But its developer tools do not display them as prominently as the Chrome dev tools do. Still, they are there, under the Tools |> Web Developer |> Service Workers menu.

From here you can unregister any Service Worker, and open the worker code in the debugger for any kind of worker (Web Workers as well). You can also trigger a Push API push event to debug Push events.

You cannot simulate events or force updating or bypassing Service Workers like in Chrome. I hope this will be possible in Firefox soon for an easier testing experience.

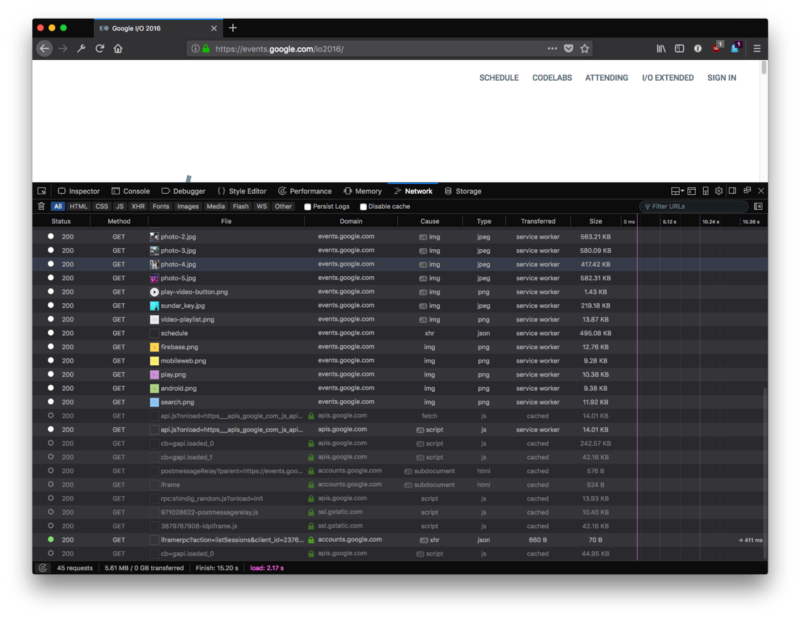

Like in Chrome, when a resource is cached by Service Workers in the Network panel of the Developer Tools using the Cache API, it lists service worker under the Transferred column:

Wrapping up

Progressive Web Apps are one of the turning points for making the Web better on Mobile and providing users with a good experience outside native apps.

Browsers, especially Chrome, provide good tooling around them.

Google also provides Lighthouse as part of its browser tooling, which can be installed separately in the Chrome DevTools. It provides automatic checks to ensure that your web app is optimally built, and includes support for Service Workers. An incredibly useful tool, don’t miss it.

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please give me some claps so more people see it. Thanks!

Interested in learning JavaScript? Get my ebook at jshandbook.com